The physical features that allow us to distinguish between a male and a female in the animal world, whatever the species, is what we call sexual dimorphism. It is these features that our brains naturally look for when assigning a sex to an animal or a person. And it is these same features that a plastic surgeon focuses on when developing feminisation or masculinisation techniques.

But what is sexual dimorphism?

Secondary sexual dimorphism refers to the features found in nature that differentiate one sex of a species from another. And it is this dimorphism, which is exclusively related to sexual reproduction, that makes it possible to differentiate a female from a male. However, these differences do not occur in all species, as is the case in some reptiles.

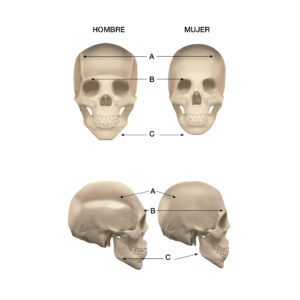

In some species the female is usually larger and stronger than the male. In other species it is the other way around, as is the case in mammals, which include humans. These specific differences allow archaeologists to know, when they find a skull or a pelvis, for example, whether they are looking at the remains of a man or a woman.

This dimorphism is a strategy of nature for sexual reproduction, to facilitate the evolution of species. In our society of today, these differentiating features of the sexes have lost much of their usefulness, but they are still very much present.

Sexual dimorphism between men and women

In humans, bone structure plays an important role in secondary sexual dimorphism. For example, the pelvis differs between men and women as a result of the female gestational function.

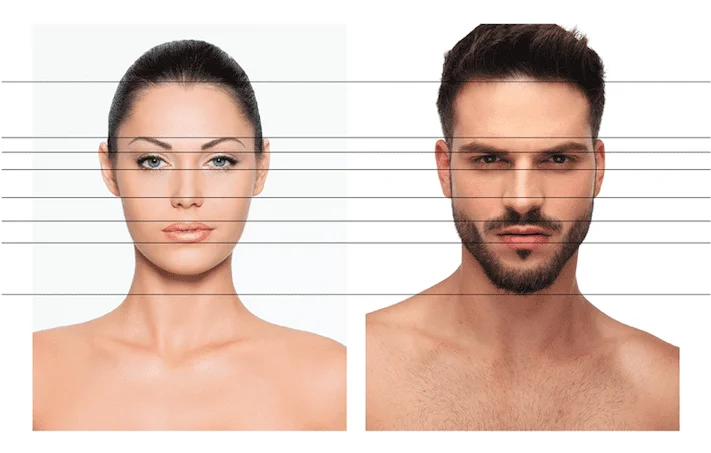

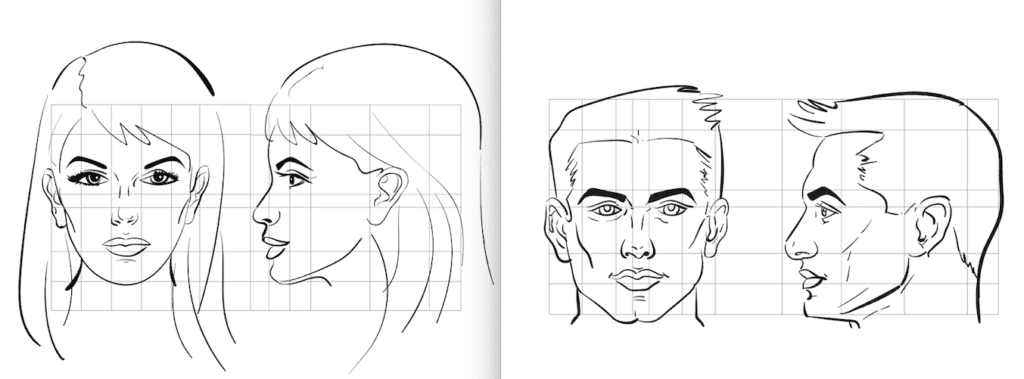

But these differences also occur in the skull. A man’s head is different from a woman’s: the shape of the forehead, the shape of the eyebrows, the hairline, the jaw, the nose, the shape of the eyes… These are aspects that, in our prehistoric ancestors, had a very different function depending on whether you were a male hunter or a female carer. These physical aspects, which evolved for the performance of certain tasks, have survived to the present day. And while they no longer have their ancestral function, they have remained in our minds as a way of differentiating between a woman’s and a man’s appearance.

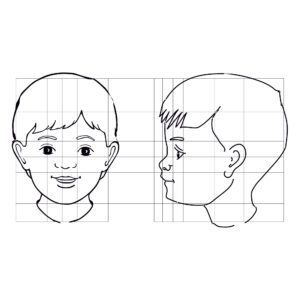

Thus, this dimorphism is determined by both genetics and hormones, but also by evolution and the roles played by our ancestors. However, secondary sexual dimorphism (dimorphism which does not strictly relate to sexual organs) in humans is not as evident as in other species.

Aspects that feminise or masculinise a face

There are many subtle or unsubtle features that make us see a face as masculine or feminine. The shape of the skull is one of the most important. The male skull has squarer and lower eye sockets, while the female skull has rounder and higher eye sockets. In addition, the male head has more pronounced brow ridges and a protrusion at the top of the eyebrows, which probably had the ancestral function of redistributing sweat to the temples when we were hunters and needed to run after prey.

Women, in contrast, who had a more sedentary role looking after offspring, did not need this sweat redistribution, but did need to demonstrate greater empathy. For that reason they had much larger eyes (more like those of their children), with fewer bony arches allowing for more mobile eyebrows so that they could communicate, express themselves and empathise better with their young.

It is this upper protrusion of the eyebrows (which is the roof of the frontal sinus) that allows us to distinguish a male skull from a female skull. This area has therefore become one of the most important sexual dimorphisms. That is why forehead feminisation is one of the most effective techniques in facial feminisation surgery, one that will also seek to increase the size and roundness of the eye sockets to achieve a feminine appearance.

Are you interested in learning more about facial or body feminisation or masculinisation?

Request an appointment with our IM GENDER team and we will answer all your questions.

Want to learn more about transgender surgery or have any questions? Feel free to contact us. We are here to help.